Experiencing childhood in Brazil, Edson Arantes do Nascimento so detested the counter-intuitive moniker his elementary school close companions used to prod him that he would battle anybody who thought for even a second to refer to him as “Pelé.”

Before he had turned into a grown-up, nonetheless, the kid had transformed the insult into a word that came to characterize soccer significance, setting out on a vocation that would create more objectives, more World Cup titles and more stunning minutes than some other.

“Individuals said, ‘Pelé! Pelé! Pelé!’ everywhere,” the kid once bemoaned long after he had turned into a man. “In any case, nobody recalls Edson. Edson is the individual who has the sentiments, who has the family, who really buckles down. Pelé is the symbol.”

The soccer player who rose from a devastated ghetto to turn into the most renowned — and, for a period, the best-paid — competitor on the planet kicked the bucket Thursday at age 82. Never distant from the game he so cherished, Pelé surrendered to different organ disappointment because of colon disease, as indicated by the São Paulo clinical focus where he had been hospitalized since late November.

“All that we are is thanks to you,” his girl Kely Nascimento composed on Instagram. “We love you interminably. Find happiness in the hereafter.”

His representative, Joe Fraga, affirmed his demise: “The lord has passed.”

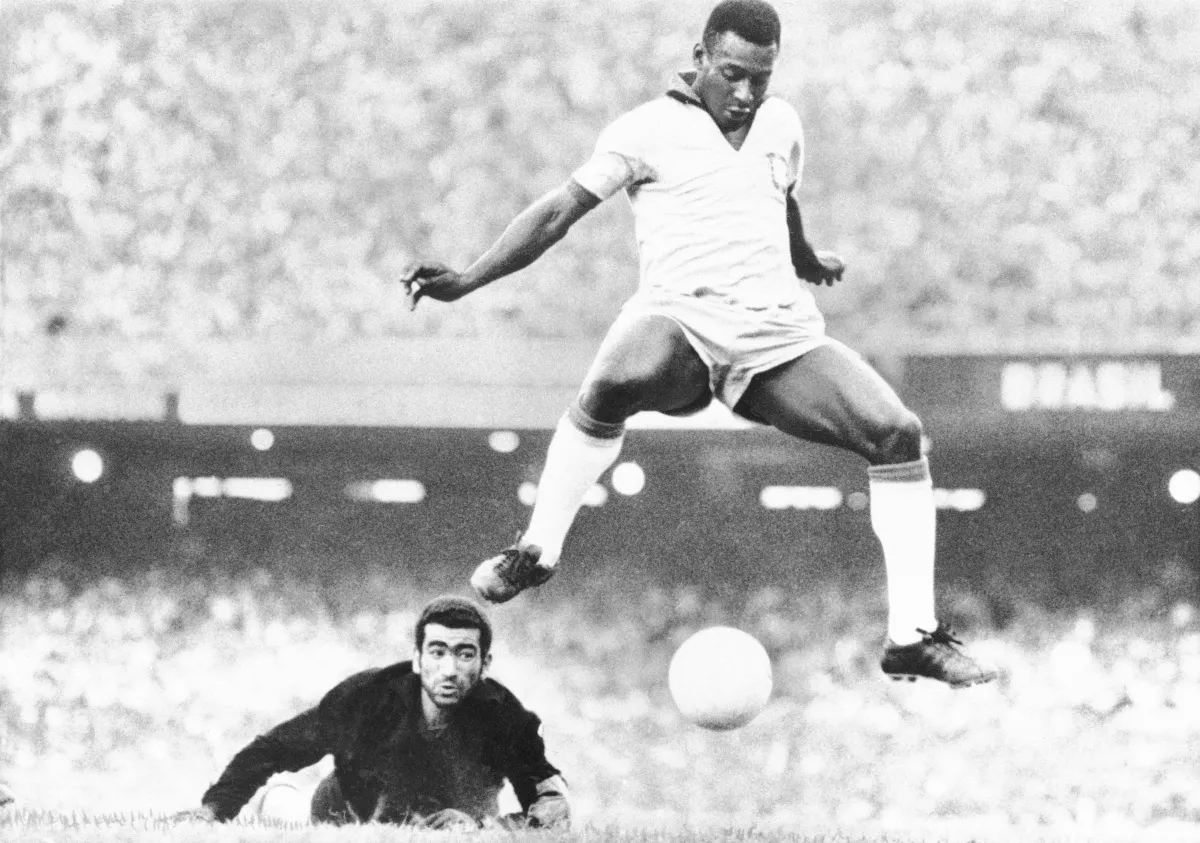

With his sharp passing, trying runs and rankling shots on objective, which he could take with one or the other foot, Pelé completely changed soccer during a 21-year profession in which he scored an uncommon 1,281 objectives, albeit more than 500 of those came in “informal” matches on trouping visits famous during his initial playing days. Accordingly, Portugal’s Cristiano Ronaldo’s 819 objectives are viewed as the untouched record, in front of Pelé’s 757.

However, numbers alone couldn’t characterize Pelé’s wizardry, which was exceptional to such an extent that militaries on the two sides of a horrendous nationwide conflict in Nigeria consented to a two-day ceasefire so that warriors could watch him play. The shah of Iran once held up three hours at an air terminal just to talk with him, the Mystery Administration let him bob a ball off President Portage’s head, and a review in the fading days of his playing profession showed that Coca-Cola was the main brand more well known than Pelé in Europe.

“Pelé is the best player in football history,” Ronaldo said. “Also, there might be one Pelé.”

“Pelé,” said the late Dutch star Johan Cruyff, a legend by his own doing, “was the main footballer who outperformed the limits of rationale.”

Pelé burned through brief period constructing his heritage, scoring in his presentation with the Brazilian public group to become, at 16 years and 9 months, the most youthful player in history to score a worldwide objective. After two years he would turn into the most youthful man to play — and score — in a World Cup.

In any case, it was the polish and delight with which he played that brought forth the Brazilian style known as jogo bonito, or the lovely game, which depends on speed, ad lib and imagination more than savage strength.

“His extraordinary mystery was impromptu creation,” said Tostão, a previous World Cup colleague. “Those things he did were in one second. He had an unprecedented impression of the game. Pelé was the best. He was just perfect.”

Edson Arantes do Nascimento was brought into the world on Oct. 23, 1940 — his introduction to the world declaration understands Oct. 21, a date Pelé demanded was wrong — in the southern Brazilian territory of Minas Gerais, his name motivated by the designer Thomas Edison.

He was known as Dico by his family, however the local children called him Pelé, mirroring his error of the name of his number one player, a Brazilian goalkeeper known as Bile. In time the insult would turn into the most renowned name in sports.

He was the oldest of three youngsters brought into the world to Celeste Arantes and Joao Ramos do Nascimento, a small time soccer player whose vocation was stopped by a knee injury. By and by, he would make a permanent imprint on soccer by showing the game to his child, who might be proclaimed an irreplaceable asset by Brazil’s leader before he had turned 21 and be casted a ballot worldwide soccer’s player of the 100 years and the Global Olympic Board’s competitor of the century over 20 years after he resigned.

The family, which incorporated an uncle and grandma, was poor and resided in a two-room house made of rescued block and washed mortar and with a rooftop that spilled. The kids wore handed down garments, frequently did without shoes and in some cases had no more to eat than one everyday feast of bread and a cut of banana.

The family’s circumstance worked on just somewhat when it moved to the intersection city of Bauru, around 180 miles west of São Paulo. Yet, in the 4th grade Pele quit his examinations subsequent to being ousted for playing soccer during the school day. He before long accepted a position fixing shoes for $2 every day to help his loved ones.

Since he was unable to manage the cost of a soccer ball, he figured out how to play on the roads utilizing grapefruits or fabric loaded down with papers and bound with string.

“The calfskin ball was over the top expensive,” Pelé told The Times in a 2014 meeting. “We used to get my dad’s old socks, my mom’s, then we’d top them off with paper and play.”

His most memorable memory of soccer’s essential spot in Brazilian culture came in 1950 when the public group, vigorously preferred to win the World Cup last in Rio de Janeiro, was irritated about Uruguay. At the last whistle one fan passed on by self destruction and three others experienced lethal cardiovascular failures.

Pelé’s dad, who had followed the game on radio, burst out crying.

“It was whenever I first saw my dad cry,” Pelé recollected years after the fact. “Then, at that point, I made a joke and told him, ‘Don’t cry, don’t cry. I will win the World Cup for you.'”

After eight years the joke turned into a prediction when a 17-year-old Pelé scored six objectives — remembering two for the last game — to convey Brazil to the first of its record five World Cup wins. Pelé was additionally essential for title groups in 1962 and 1970, making him the main individual in history to win three World Cups.

“I let myself know before the game: He’s made of skin and bones very much like every other person,” said Italian safeguard Tarcisio Burgnich, who had the unenviable assignment of checking Pelé in the 1970 last. “However, I was off-base.”

The gloat to his dad wasn’t the only one Pelé’s ability followed through with. At the point when he was just 15, his childhood group mentor encouraged the overseers of the impressive Brazilian club Santos to sign Pelé, demanding he would before long be “the best football player on the planet.”

The chiefs tuned in and throughout the following 18 years Pele drove the group to six public titles and triumphs in six global competitions before his retirement at 33. Pele acquired almost $1 million in his last season in Brazil in 1974 — what might be compared to more than $6.3 million today — and given everything to youngsters’ foundations.

However, a progression of terrible speculations left him close to monetary ruin several years after the fact, so Pelé got back to soccer, marking a three-year, $4.5-million agreement with the New York Universe of the striving North American Soccer Association. He proceeded to score 31 objectives and bring home one more association championship while enthralling even the most fatigued U.S. avid supporters.

A then-record 10 million Audience members watched the live transmission of his 1975 Universe debut. With Pelé, the association’s typical participation bounced almost 80%, driving the Universe out of little Bringing down Arena on Randall’s Island to Yankee Arena, where they frequently played before bigger groups than the ball club.

Toward the finish of Pelé’s last season in 1977, the group had moved to Goliaths Arena, where it drew 77,691 for a season finisher game, at the time the biggest group to go to a soccer match in the US.

He played his last authority game — and scored his last objective — sometime thereafter, playing one half for the Universe and one half for Santos at Monsters Arena on a day that was mixed to such an extent that a Brazilian paper, taking note of the stormy circumstances, said “even the sky was crying.”

After Pelé left, the groups vanished, tumbling to a normal of under 13,000 when the NASL collapsed in 1984. In any case, the inheritance he left behind was acknowledged by quite a few people for preparing for the U.S. to play host to the 1994 World Cup, still the most monetarily effective and best-went to soccer competition ever.

Assuming that retirement kept Pelé off the field, save for incidental cause matches and shows, it didn’t get him far from soccer or out of the public eye. Nor might his VIP at any point be restricted to one nation or even one sort.

He was the individual visitor of no less than three popes, six rulers, eight presidents, 15 lords and multiple dozen different heads of state. He was a Unified Countries diplomat for biology and the climate, an UNESCO generosity representative, and in his job as Brazil’s priest of sports he proposed regulation to lessen debasement in soccer, a bill that became known as “Pelé’s Regulation.”

He composed a few collections of memoirs, acted in basically twelve movies and a television series, made the soundtrack for the 1977 film “Pelé” and was respected with knighthood in Britain, a postage stamp in North Korea and in the tune “Ghetto Supastar” by the American rapper Pras.

There appeared to not be anything he was unable to do and no item he wouldn’t pitch while likewise investing energy as a telecaster and sports journalist. Indeed, even in his 70s, Pelé kept up a rebuffing limited time plan, frequently visiting three or four mainlands per week. Assessments of his yearly profit drew nearer $30 million.

If you are interested in Pele-Inspired designer products, please see more at Pele Collection here!